By Gregg Andrews

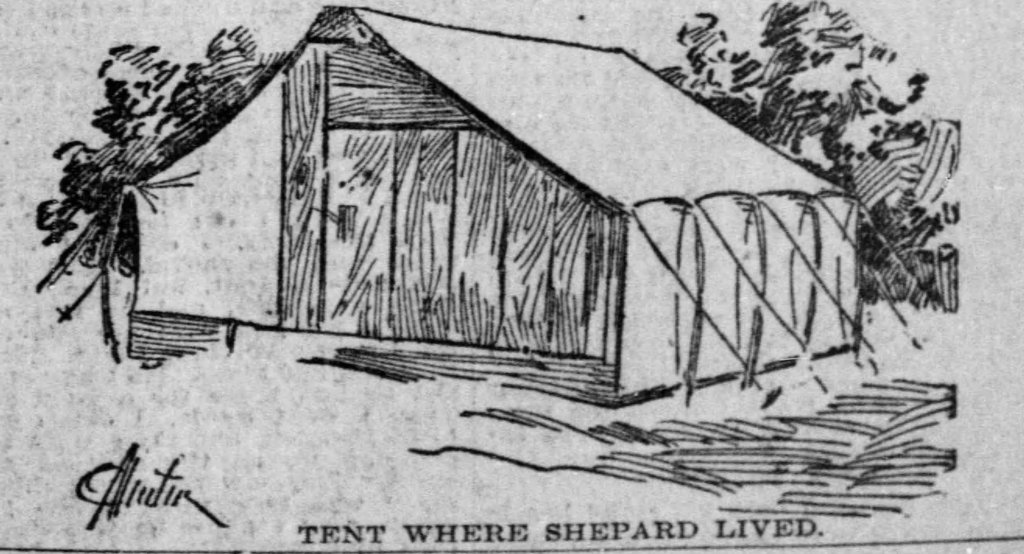

On December 29, 1894, as Lizzie Leahy lay dying in the City Hospital, the startling discovery of Tom Morton’s corpse with his pockets turned inside out in a shallow levee grave sent further shock waves up and down the St. Louis shoreline. Police arrested Robert Noble Shepard, an out-of-work young glass blower formerly employed by Anheuser-Busch. Shepard, without a steady job in the Depression of 1893, had left his pregnant wife, Maggie, and their three-year-old son, Robert, with her parents in Belleville, Illinois, while he searched for work. First, in East St. Louis, where he pitched a tent on the shoreline, and then in St. Louis. Maggie said he treated her well, but her father, George A. Wolf, a German-born coal miner and Union Civil War veteran, had nothing good to say about him. Shepard was widely disliked in Belleville. His tent on the south St. Louis riverfront was about 100 feet from where Morton’s little terrier led police to his corpse. Reportedly, Shepard often visited Tom and Lizzie’s shantyboat. In fact, they once hired him to fix a leak in the roof of their boat. From statements made by area teenage boys who knew them, it appeared that Tom and Shepard sometimes drank together, and that Tom and Lizzie often quarreled, perhaps over Tom’s drinking.

Shepard puffed on a cigar and seemed unfazed when police handcuffed him. He joked and chatted with the arresting officers. Chief Detective William Desmond, accompanied by detectives “Big Mike” Kelleher and Johnnie Howard, escorted Shepard to the city morgue to identify Morton’s body, which was still covered with silty sediment from the shoreline grave. With newspaper reporters and morgue officers on hand, all eyes riveted on Shepard as Chief Desmond forced him to take a good look at the wounds on the battered and badly cut corpse. Shepard remained cold, cagey, and detached, at first not even acknowledging it was Tom. He admitted to no involvement in killing him.

Later, after Chief Desmond “sweated” Shepard for an hour in the Four Courts building, the suspect weakened and offered the first of about four slippery confessions to the crime. He claimed that when he went to the shantyboat, Lizzie was drunk and offered him a drink of whiskey. Tom returned home, stormed onto the boat, and angrily hurled a brick at him, but the brick struck Lizzie instead. According to Shepard’s initial confession, he hurried out the door, but Tom followed in hot pursuit and fired at him with a revolver. Tom, still armed, stormed over to Shepard’s tent, where Shepard hit him with a shovel several times and killed him in self-defense, later dumping the body into a shallow grave he dug on the riverbank with the help of a couple of levee bums.

In the rush to print, some of the initial newspaper coverage of Shepard’s murder of Tom and the brutal assault on Lizzie was riddled with inaccuracies, speculation, and gossip. So, too, was Shepard’s confession filled with holes and contradictions. His version of events didn’t square with the evidence. Investigative detectives operated on the theory that robbery was the motive for Shepard’s murder of Morton. On January 2, 1895, Shepard added a new version of his confession in which Tom attacked him when he caught Lizzie and him drinking whiskey together in an intimate, compromising moment in their shantyboat bed. In a rage, Tom allegedly attacked Shepard, who fought him off. For the first time, Shepard admitted he struck Lizzie, but he claimed he did so only to get her out of the way when she tried to stop him from going after Tom in the fight. Shepard fled the shantyboat as Tom fired a shot at him. Later, Tom came to his tent, fired at him again, and grabbed a hatchet as they continued to do battle. Shepard got the upper hand as they grappled over the hatchet, and he hit Morton with it four or five times. “I was full of whisky and I’m devilish when I’m full of whisky,” Shepard told Chief Desmond.

Lizzie was delirious much of the time in City Hospital, but she gave a sworn statement to the coroner in the presence of Dr. Heine Marks. Shepard was the last person with her before she was beaten into unconsciousness, but she maintained she did not know who struck her. She emphatically denied she was drunk at the time she was struck, telling a Post-Dispatch reporter: “I never tasted a nickel’s worth of whisky in my life.” Lizzie refuted Shepard’s claim they were intimately involved: “I have never been intimate with Noble Shepard at any time that I know of.” Lizzie called Shepard a liar, but he insisted she lied on both issues. Alpha Gilroy, Tom Morton’s poor, ailing mother in Newport, Kentucky, first learned of her son’s death in a Newport newspaper. With financial help from friends, she made her way to St. Louis, where she stood and wept at Lizzie’s hospital bedside and met her parents. When Chief Desmond showed her a watch recovered by a detective from a shop where Shepard pawned it, she identified it as her son’s and broke down in a flood of tears. She told Desmond that about two months earlier, she received a letter from Tom indicating he would be home for Christmas. The city undertaker, aware of Mrs. Gilroy’s limited resources, offered to ship Tom’s body to Newport free of charge.

Detectives discounted Shepard’s story that Tom caught him in a compromising position with Lizzie on the bed. On January 3, a coroner’s jury determined that Shepard killed Morton by fracturing his skull with a hammer and hatchet. Shepard was bound over for the grand jury. In the meantime, Lizzie’s condition deteriorated as she sank into a coma for ten days before she died on January 21st. Now facing double murder charges, Shepard, upon learning of her death, told a reporter, “I could not help it. I did not mean to kill her.”

Shepard showed no remorse or sympathy for his victims. Locked in his cell at the Four Courts, in fact, he wrote poetry and doggerel about how he murdered Tom and Lizzie. Incredibly, he cracked jokes about his crimes to stunned guards and detectives, proudly reciting some of the verses he intended to publish as a song to sell to make money off his own murderous deeds. When taken to Chief Desmond’s office with a Post-Dispatch reporter present, Shepard recited aloud some of the endless verses to the unfinished song. One of the verses read: “Lizzie Morton, said she: Let my Tommie be.” Thinking her Tommie was dead. She shut my wind off, and that made me cough—and that’s when I cracked Lizzie’s head.” Basking in the glow of his own recital performance of the verses, Shepard leaned back in his chair afterward, lit a cigar, and puffed away contentedly. “There was something absolutely fiendish and uncanny about the man’s mirth,” observed the reporter on January 6, 1895. “One would have thought he was reading a funny story, rather than the story of one of the most horrible crimes on record.” The reporter concluded that Shepard “must either be crazy, or a heartless, cold-blooded wretch.” (TO BE CONCLUDED)

Leave a comment