By Gregg Andrews

On an “uncommonly dark” night just south of Hannibal, March 19, 1835, wicked, murderous blasts from a double-barrel shotgun shattered an enslaved “runaway’s” sparkling vision of freedom in the Mississippi River bottomlands of Ralls County, Missouri. Henry Auburn Harris fired buckshot and ball into the back of the head and neck of nineteen-year-old “Anderson” as he made a mad dash toward the river from the detached kitchen on the Harris Plantation. Harris held the office of Ralls County Treasurer, and John Steel, of adjacent Pike County, was Anderson’s owner. In Saverton, justices of the peace, Hosea Northcutt and Tyre A. Haden, held a hearing into the killing, but there was no coroner’s inquest, only a hasty burial of Anderson the next day. Neither was there a criminal prosecution of Harris, a “fractious,” hot-tempered, and unmarried twenty-seven-year-old from a Richmond family known for unspeakable brutality when it came to flogging, whipping, and beating slaves.

For nearly two centuries, the blood-splattered fate of Anderson has remained a dirty secret. If not for Steel’s civil lawsuit against Harris for damages, and if not for my research, the case might have remained buried for another two centuries in local court records. Yet another lost river story that never got told! I want to thank Ralls County Collector, Tara Thompson Comer, of Saverton, and David Snead, archivist for the Missouri Secretary of State’s Local Records Preservation Program, for helping to locate the digitized records of the case. After a change of venue from Ralls to Pike County, Steel’s suit ended up in the Callaway Circuit Court in Fulton. The digitized files include transcripts of the records from the circuit court in Bowling Green. Steel was forced to wait more than two years for compensation in the case while Anderson had to settle for a bottomland grave and a swift burial “in a Christian-like manner.”

Henry Harris, born on December 25, 1807, grew up in a family with vast landholdings and business operations that used enslaved labor. His father was Benjamin James Harris, an engineer, inventor, and tobacco manufacturer in Richmond, Virginia, and his mother was Sarah Ellyson Harris, of Prince George County. When Henry was a child, his father whipped a fifteen-year-old “slave girl” to death. William Poe, a former slaveholding merchant from Richmond who knew the Harris family, attended the trial. “While he was whipping her,” Poe recalled, “his wife heated a smoothing iron, put it on her body in various places, and burned her severely. The verdict of the coroner’s inquest was, ‘Died of excessive whipping.’” Harris was acquitted, but a few years later, according to Poe, he “whipped another slave to death. . . [who] had not done so much work as required of him. After a number of protracted and violent scourgings, with short intervals between, the slave died under the lash.” Once again, Henry’s father got away with murder, “because none but blacks saw it done.” Benjamin wasn’t finished yet. Poe recalled that he later whipped another slave so severely and repeatedly for not working hard enough that “the slave, in despair of pleasing him, cut off his own hand.”

The Ralls County killing of Anderson took place on the Harris Plantation between the Mississippi River villages of Hannibal and Saverton. The plantation, regarded by some as the northern part of Saverton at the time, was mentioned by the narrator in the 1944 movie, The Adventures of Mark Twain. In an earlier blog, “Iron Shackles and Old Rock Houses on the Mississippi River” (April 22, 2022), I introduced readers to a mysterious rock house on the bottomland tract once known as the Harris Plantation. The rock building at the south end of “Monkey Run,” a river hamlet created in 1907 for toilers at the nearby Atlas cement plant, was still standing when I was a child. I stared at the rock house nearly every day when I walked my newspaper route, 1959 to 1964. The mysterious building, a short distance from the main house, seemed a relic from an earlier century. The disturbing sight of iron shackles when I peeked into the building one day remains etched in my memory. After carefully studying the depositions and other court records in this case, I now believe that the old rock building, in its earliest form and use, probably was the detached kitchen where the enslaved prepared meals for Harris and his guests. And, where Harris, with adrenalin pumping and both barrels of his shotgun loaded, cornered Anderson, drew him outside, and shot him as he ran toward the river.

What were the circumstances that led to the killing of Anderson? In November 1834, Elijah N. Hascall (Haskell) hired Parker H. Novel to cut 200 cords of wood at 50 cents a cord on Sny Island, about two miles north of Saverton near the Illinois bank of the Mississippi. To increase his profit, Novel leased two male slaves, Charles and Anderson, from Steel at a rate of ten dollars per month to chop wood under his supervision on the vast island in the upcoming winter months. Novel, who lived about a half mile from Steel, was previously employed as the overseer of Steel’s farming operations. Novel had known Anderson, who stood six feet tall and weighed about 180 pounds, for four years. He described him as “humble to a white man, as much as any negro.” Michael Jones, a neighbor who was among those deposed in Steel’s lawsuit, recalled that Anderson was in his house “a great many times—he was humble to me always—and I never knew of his being other wise to any other white person. . .The only complaint I ever heard of him was that he was fond of going about at nights.” In the months before Novel leased him to chop wood, Anderson reportedly grew “outdacious” with a growing fondness for the freedom that darkness brought when neither master nor overseer stood over him. Milton Scott, a Saverton township farmer, complained that Anderson was “saucy and impudent to white folks,” including himself “on one occasion while paddling the river in a canoe.”

The mile-wide river called out to Anderson. On one occasion, shortly before Steel leased him to work on Sny Island, he had to retrieve Anderson from jail in Quincy, Illinois, where authorities held him after he crossed the Mississippi in a bid for freedom. Later that night, Anderson ran off again but was recaptured. Steel hired him out to Novel from November 1834 to March 1835 in hopes that isolation and hard work on the gloomy, uninhabited Sny Island might curb his nighttime running around. During the time Anderson was hired out to Novel, they paddled back and forth across the Mississippi routinely. When not chopping wood, they stayed on Steel’s farm and had their clothes washed nearby. When the weather turned bitterly cold in late February 1835, Novel sent Anderson back across the river with a note indicating to Steel that he no longer needed his labor. Anderson fled from Steel the very next morning, once again working his way toward the river. It would be no easy paddle to freedom, but Anderson knew the river. Steel, determined to recapture him and “take him down the river to sell,” alerted neighbors to be on the lookout for him. In a conversation with Horatio Penn, Steel suggested that he use his slave to lure Anderson into the house as part of a trap if he showed up there. According to Joseph Abbington, who overheard the conversation, Steel instructed Penn “to put the dogs on him [Anderson] or shoot him in the legs with shot” if he resisted.

One of Henry Harris’s own slaves also had fled the plantation at the time. Harris, who asked Judge Haden and John Conn to search for him, blamed Anderson for enticing him to run away. Haden, when asked later if he ever heard Harris make a threat against Anderson, replied in a sworn deposition: “He told us to take our guns with us–and that if the negroes run to shoot down [Steel’s] negro Anderson. . . and that his. . . would come home, that he did not believe his negro would ever have run away if it had not been for Anderson.” According to Haden, Harris added “that if they came about him and he ordered them to stop and they did not that he would put a load into them pretty quick.”

Haden, Joel Epperson, and several other men were staying overnight at the Harris Plantation on the night of the killing. Harris operated a country store on his place, and it was common for distant travelers and customers to stay overnight with him. Among them that night was Zedekiah Merritt, who already had gone to bed in the company of Harris and Thomas H. Johnson. In Merritt’s sworn statement, he said that Harris got out of bed to answer a knock on the door at about ten o’clock. Merritt did not overhear the conversation, but he learned it was “Stepto,” one of Harris’s slaves, at the door. Harris earlier promised “Stepto” he would get a reward from Steel if he provided information that led to Anderson’s capture. “Stepto” informed Harris that Anderson was in the kitchen with a club. Harris loaded his double-barrel shotgun, picked up a piece of rope, and asked Merritt to go outside with him to the kitchen. Harris handed him a pistol and a shovel handle, and off they went. According to Merritt, Harris intended to hold the gun on Anderson until Haden and other overnight guests came out of the house to tie him up.

Harris, with one barrel loaded with duck or turkey shot, and the other with shot and a ball, stepped in front of the door to the kitchen while Merritt stood near the chimney. Anderson was warming himself by the fire. Merritt did not see what happened next. According to Harris, Anderson did not heed his order to submit, instead charging toward the door with a large piece of elm timber as a club. Harris claimed that he drew back several paces from the door to allow Anderson to come outside, and that he feared stray shot might hit one of his own slaves if he fired at the legs of Anderson in the kitchen. He later told Constable James Fuqua that the first shotgun blast hit the kitchen door, the facing, and logs, about knee high. As Anderson ran for his life toward the river, Harris emptied the other barrel, killing him with a ball and shot to the back of the head and neck. Insistent that he aimed to shoot Anderson in the legs, Harris pleaded that the victim must have been squatting when the ball and shot struck him. At Harris’s command, “Stepto” took a lantern and searched nearby to see if Anderson had been hit. He didn’t have to look far. The bloody victim lay about thirty steps from the kitchen door with the club lying near his right hand. By the time Haden and others came running out of the house, awakened by Harris’s loud calls for help, it was all over.

William Pitt, who arrived at the plantation around dusk the next day, said Anderson’s body was already in the ground. Satisfied after talking to Harris that there was no need for an inquest, Judge Haden claimed he authorized the burial, but it was widely reported that Harris encouraged it. On March 31, Ralls County Sheriff Chapel Carstarphen’s deputy, Robert B. Caldwell, arrested Harris, who claimed self-defense. Besides, Harris insisted that he was perfectly entitled to kill a runaway slave. Although Harris was a Ralls County official of influence, wealth, and power, he complained that he could not get a fair trial in Steel’s civil suit against him in New London. The circuit court granted him a change of venue to Bowling Green, but the case was later moved to the Callaway Circuit Court in Fulton.

Harris pleaded that he intended to capture Anderson and return him to Steel. He based his defense partly on grounds that Anderson was “a runaway slave of bad habits & practices and of desperate character” who planned to flee the state. Parker Novel’s testimony was perhaps the most damning against Harris. Novel, known widely for his truthfulness and veracity, provided two sworn statements under cross examination, but as Harris noted in a letter to Abiel Leonard, his lawyer in Columbia, “Every question asked Novel makes the matter worse.” One of the legal arguments of Harris’s attorneys amounted to a twisted use of the “Once Free, Always Free” doctrine pertaining to slavery in Missouri. An 1824 Missouri statute allowed the state’s enslaved to sue for freedom if they were taken to a territory or state where slavery was banned, even if they returned to a state where slavery was legal. When the monumental Dred Scott case, filed in St. Louis in 1846, reached the Missouri Supreme Court, however, the court reversed course in an 1852 decision that afterward made it nearly impossible for such “freedom suits” to succeed. Harris’s lawyers argued unsuccessfully that since Anderson was hired out to Novel on Sny Island (Illinois) in the winter of 1834-1835, he was free, no longer the property of John Steel, who therefore was not entitled to financial compensation from Harris.

It took two-and-a-half years for the civil suit to reach its conclusion in the October 1837 term of the circuit court in Fulton. The jury awarded damages in the amount of $1500 to Steel plus court costs for the loss of his slave. The court denied Harris’s request for a new trial. In the years ahead, Harris expanded his extensive landholdings in northeast Missouri, married Margaret Jane Davis at age 43 on January 2, 1851, and raised three children. When he died in Hannibal on September 11, 1875, he left a sizeable estate for his heirs. To his son, Ben James Harris, he included in his bequests the double barrel shotgun. The same reckless temper that led Henry to kill Anderson in 1835 lived on in family memory. Philip C. Smashey, whose grandfather, Samuel Talbot Smashey, was a nephew of Harris’s, remembered a story that was told to him by his father, David Morton Smashey. On one occasion during the Civil War, Union troops visited the Harris Plantation and helped themselves to provisions and whatever they wanted. Henry was furious. “The next morning,” Philip Smashey recalled to Dorothy Eichenberger in 1990, “my grandfather, Samuel, came to the Plantation and found Henry Harris in a rage. He showed my grandfather a canon he had hidden in a clump of bushes. Harris told my grandfather that he was going to plant the canon on the banks of the river and sink the first Union boat that came along. My grandfather told Harris, ‘Henry Harris you won’t try to sink more than one of those Union boats.’”

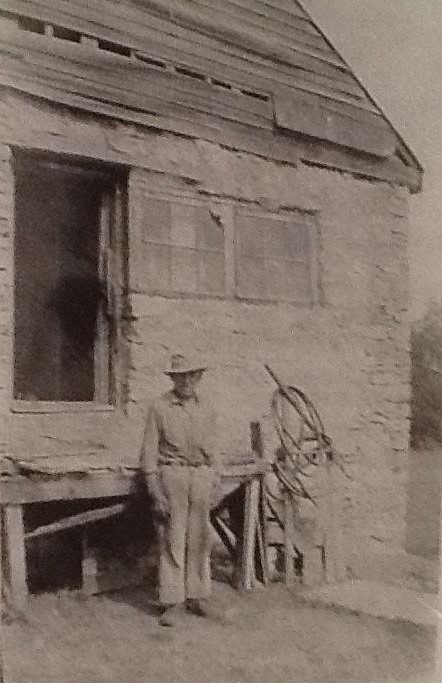

On one of our trips back to my roots in Monkey Run, Victoria Bynum took what might be the last photo of the old rock building on the Harris Plantation, circa 2002-2006. Little did either of us know that she was taking a photo of the crime scene where Henry A. Harris shot and killed Anderson just beyond the rock building in 1835. Nor did we know that the property owner would soon tear down the building. The property, of course, had changed markedly over the course of nearly two centuries, but Vikki’s photo captured the Mississippi River in the background and the rock building, although it was partially hidden by a white shed. When I wrote and recorded the song, “Gonna Be Free,” available on the link below, I knew nothing of the murder. Funny how fate, karma, and a search for the truth sometimes come together.

Sadly, we know little about Anderson, but the evidence in this case makes clear his determination to use the Mississippi to escape enslavement as he grew into manhood. Did he develop a network of Underground Railroad contacts on the Illinois side? When he “ran around at night,” was he visiting others who were enslaved in the area? Did he have a wife, or perhaps children who was enslaved on a neighboring farm? Did he intend to organize a “stampede” of freedom seekers? Was he studying the stars and the Big Dipper and marking signs to guide him on a northward journey? Finally, what were the topics of conversation in the detached kitchen that night, and did “Stepto” regret his role as informant? These questions and so many more beg for answers nearly two centuries after the lights of freedom flickered and went out as Harris emptied the second barrel into the back of Anderson’s head and neck in the darkness.

Selected Sources: John Steel v. Henry A. Harris, 1836, Callaway County Circuit Court; Virginia Lee Hutcheson, Tidewater Virginia Families (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2004), pp. 474-475; Theodore Dwight Weld, American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses (New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1839), p. 26; Marriage of Henry A. Harris and Margaret Jane Davis, January 2, 1851, Missouri, U.S., Marriage Records, 1805-2002, Ralls County; Will of Henry A. Harris, July 25, 1873, Ralls County, Mo.; 1840, 1850, 1860 United States Federal Censuses, Slave Schedules, Ralls Co.; Philip C. Smashey to Dorothy Eichenberger (author’s possession), January 12, 1990.

Leave a comment