By Gregg Andrews

Born into slavery on June 24, 1859, in northeast Ralls County, Missouri, Jesse Stepton Woods and his mother, Nancy Woods, left the bottomlands between Marble Creek and Salt River, tributaries of the Mississippi, to celebrate a life of freedom in nearby Hannibal. They reunited with Nancy’s older children and her father, Nathan McDowell (often misidentified as McDaniel or McDonnell). Jesse, the baby of the family, bore the name of his deceased father. Little is known about his father, but I believe he might have been the slave known as “Stepto” on the river plantation of Henry A. Harris. [See my earlier blog post: The Murder of a Slave. . .].

The Mississippi River was a crucial variable in the family’s history from slavery to freedom. In 1825, Moses D. Bates used Jesse’s enslaved grandfather, Nathan McDowell, to do the hot, hellish work of a fireman on the General Putnam, one of Bates’s early steamboats, on a trading run from St. Louis to Galena, Illinois. Jesse’s mother was a washerwoman, and his brothers were teamsters on Hannibal’s busy riverfront, hauling wet logs to the lumber yards of Herriman & Waples, S. T. McKnight & Co., and the Northwestern Lumber Company. During the Civil War, Jesse’s oldest brother, Preston, had been wounded in combat in the Eighth Infantry Regiment of the United States Colored Troops.

At age 10, Jesse was apprenticed to a Hannibal tobacco manufacturer, and at 15, he worked for an area farmer. Hell bent on an education, Jesse learned to read and write after paying the farmer a dollar for a copy of the alphabet. A member of Hannibal’s African Methodist Episcopal Church (Allen Chapel), he entered the ministry in 1881 and founded the Bethel A.M.E. Church in Beloit, Wisconsin. Woods, soon followed by George Woodson, of Hannibal, were the first Black students to attend Beloit College. About three years later, Woods moved to Evanston, Illinois, where he founded Glencoe’s St. Paul A.M.E. Church and graduated four years later from Northwestern University’s Garrett Biblical Institute. On June 23, 1891, Rev. Woods married Amanda J. De Pugh, one of four teachers at the Lincoln School in Quincy, Illinois. Her father, Henry, was an A.M.E. minister near Alton. Amanda, described as “cultured and amiable,” remained active in A.M.E. circles after she resigned her Quincy teaching position and married Woods.

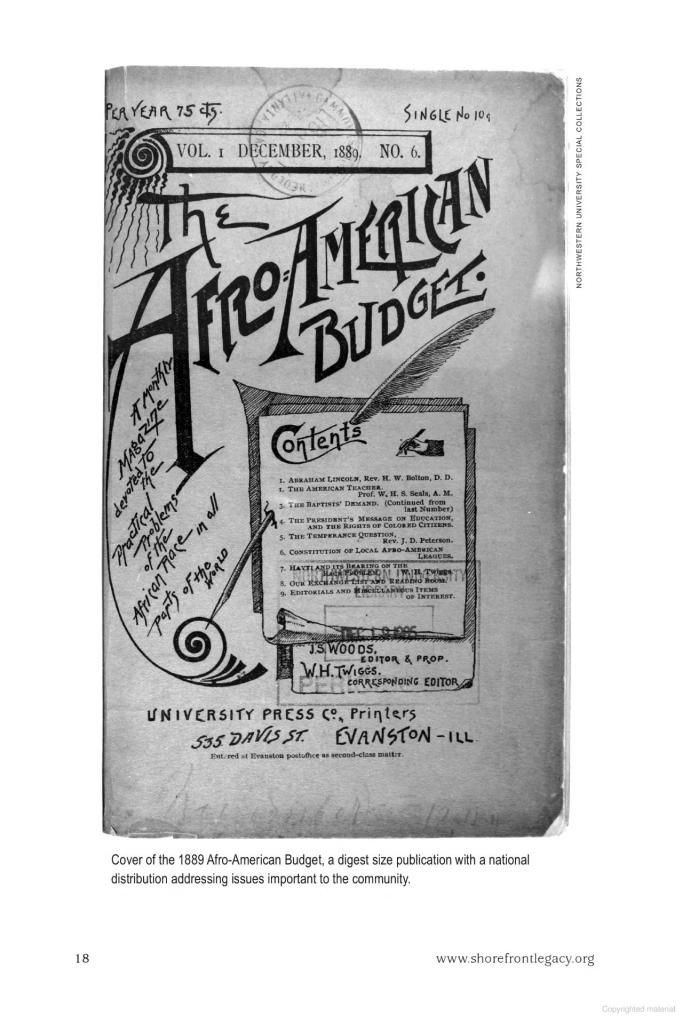

In Evanston, with the help of William H. Twiggs as corresponding editor, Woods founded the Afro-American Budget, which survived less than two years. The Budget, featuring articles by Black intellectuals and political figures like Frederick Douglass, T. Thomas Fortune, and others, helped to catapult Woods onto the national political stage. A powerful, entertaining speaker, preacher, and leader of a musical quartette, Woods blazed a trail across Illinois, Iowa, Wisconsin, and beyond to raise money and build churches. He held church assignments in Beloit, Madison, and Milwaukee, Wisconsin, as well as Champaign, Evanston, Decatur, Pontiac, Quincy, Peoria, and Springfield, Illinois. He was selected as presiding elder of the Peoria A.M.E. district.

When the Illinois branch of the Afro-American Protective League was founded in 1895, Woods was chosen as its President. A Republican, he urged unity against lynching, mob violence, and racial exclusion from businesses, schools, and jobs. In a battle against the “Lily White” faction of the Republican Party, Woods made an unsuccessful bid to represent Peoria in the Illinois legislature in 1896. A friend and protégé of Booker T. Washington’s, Woods emphasized practical solutions as he appealed to monied whites for support. Like Washington did in his 1901 autobiography, Up from Slavery, Woods called for self-help, vocational training, and schooling as practical tools of growth and pride among the formerly enslaved. Increasingly conservative, he opposed a frontal political challenge to segregation for strategic reasons.

In 1912, Woods became pastor of the St. Mark A.M.E. Church in Milwaukee, but he resigned five years later to open the Booker T. Washington Social and Industrial Center in Milwaukee on November 27, 1917. The center included an Industrial League Club that provided a free employment bureau for Black men and women. It offered women training in domestic science, catering, serving, manicuring, and hair dressing. Designed to assist Black migrants from the South, the building had forty-eight living rooms with a library, café, dining room, music room, reading room, game room, smoking room, five bathrooms, and more. He moved into the building with his wife and two daughters.

Woods, held in high esteem by many, had his share of critics, including some of his own parishioners in Peoria who accused him of financial mismanagement and overly ambitious undertakings. In Springfield, his lavish lifestyle drew criticism. Others disagreed sharply with his unabashed support for American imperialism in the Philippines and his uncritical praise for presidents Abraham Lincoln and William McKinley. His bootstrap political philosophy was unpopular among many Black leaders. Like Tuskegee Institute, the Milwaukee center depended on the financial backing of white industrialists.

In 1915, Rev. Woods began to experience problems with his vision. He lost his eyesight during the final two decades of his life but stayed active as a speaker. When the Great Depression hit, he endorsed the “Back to the Farm” movement. As he railed at labor unrest and radicalism, he urged the Black masses to return to the land to make a living. Woods became politically irrelevant and out of touch with the economic and social realities confronting the nation. He died on November 25, 1934.

Despite Woods’s remarkable climb from poverty rooted in Hannibal-area slavery, his life of political and religious activism via the A.M.E. Church is unknown today in the Hannibal area. Beloit College’s website does not include him or George Woodson among its first Black students. Except for a few historians who have mentioned Woods briefly, he has been under studied by scholars. In an upcoming blog, I will follow up with a post devoted to his daughters, who made their mark in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles.

NOTE: The newspaper, genealogical, and census records I used for this post are too numerous to mention here, but for a brief sketch of Woods’s early history, see the Chicago Chronicle, Dec. 22, 1895, p. 10. The featured image in my post was taken from Robert A. Sideman, African Americans in Glencoe: The Little Migration (The History Press, 2009). The photo is in the Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Library, Evanston, IL. On Rev. Woods’s founding of the Booker T. Washington Social and Industrial Center in Milwaukee, see Joe Trotter, Black Milwaukee: The Making of an Industrial Proletariat, 1915-1945 (University of Illinois Press, 1985), pp. 64-65.

Leave a comment