By Gregg Andrews

Johnny W. Wiggs was 13 when Frank L. Kelly, President of the Hannibal Humane Society, and attorney F. W. Neeper showed up at his family’s shanty in 1911. The child rescue mission to Monkey Run, a bottomland section of the cement manufacturing town of Ilasco, came after Kelly received complaints from neighbors of the Wiggs family. On that hot, muggy Saturday afternoon in mid-July, Johnny and his sisters were sitting in the grass under a nearby shade tree. Their father, thirty-three-year-old Madison Matthew Wiggs, was nowhere to be seen when Kelly and Neeper stepped out of the attorney’s 1910 Maxwell Model G touring car.

Kelly and Neeper poked around inside the house. What they saw disturbed them. The home was “almost as filthy as a hog pen with hardly any furniture or anything else,” Kelly reported. The children, forced to rely on neighbors for food, were “dressed in rags and apparently half-starved.” Kelly soon located and confronted their father, who was angered by the interference in family matters. In “one of the saddest cases” Kelly had seen, he threatened to take custody of the children unless the father made satisfactory arrangements for them by the following day.

A recently divorced day laborer, Wiggs reportedly drank up what little money he earned, and from time to time, you could find him behind bars in the Ralls County jail for public drunkenness and disturbing the peace. A week after the ultimatum by Kelly, he signed away his legal rights to the children, who continued to stay with him until Kelly found a place for them. Hannibal’s Home for the Friendless was at full capacity with no spaces available at the time. The children’s elderly grandfather, John A. Wiggs, a truck gardener and former Ralls County deputy sheriff, lived nearby, but he was unable to care for them. Their mother, Daisy Wooten Wiggs, had already left town. She was in a new romantic relationship and pregnant at the time she divorced their father in October 1910. She immediately remarried and moved with her new husband, Ed Frost, to Versailles, Illinois, where she soon gave birth to their daughter, Irene. In Daisy’s divorce petition, she charged Wiggs with extreme cruelty and claimed he ran her off with a pistol and threatened to kill her if she tried to take the children. When Kelly and John Foley, of the humane society, returned to Monkey Run in a borrowed buggy to take the children on Sunday, July 30, 1911, Johnny hid in the brush, refusing to be taken. Kelly and Foley, promising to return later for him, loaded Josephine (Josie), age 10, Ida Belle Mae [Leona] (8), Mattie (5), and Hattie (3), into the buggy and took them to Hannibal.

The Humane Society had trouble finding homes for the girls. When Kelly first took custody of them, he reported, “They were not only filthy, but literally covered with vermin, and almost half naked.” At her home near Oakwood, a Hannibal woman, Mrs. [Rose?] Peters, cleaned them up, fed, and cared for them temporarily for eight dollars a week. A family in Palmyra took one of them for a short while but soon returned her. With the help of the Provident Association, Kelly then turned the girls over to the Children’s Aid Society of St. Louis, which found foster homes for them. The details and locations of their placement remain mostly unclear. Even the question of how many Wiggs children were taken by the Humane Society is a bit confusing. Newspaper accounts, census records, and family genealogical sites on Ancestry.com and Find a Grave sometimes contradict each other. In Josie’s case, it was particularly hard to find someone to care for her. She suffered from a congenital spinal deformity. The Children’s Aid Society in St. Louis assumed responsibility for her with the financial help of a Sunday School class at the Pilgrim Congregational church in St. Louis. Josie ended up in the household of William and Laurice Carpenter in Dayton, Ohio, where she died at age 21 on February 5, 1923.

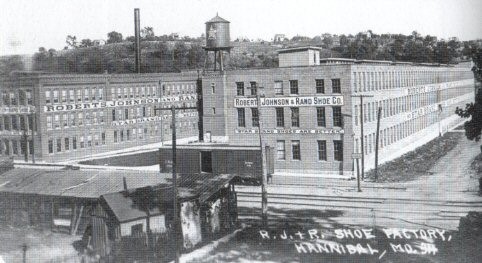

From the evidence I’ve seen so far, it’s not clear where Johnny stayed after his sisters were taken away. He might have remained outside the clutches of the Humane Society as he came of age in the Ilasco area. On September 21, 1912, a freight train struck and killed the children’s father as he was walking along the railroad tracks on his way to do some work for David R. Scyoc, north of Hannibal. John, a World War I veteran, worked as a brakeman on the CB&Q Railroad after the war, but in 1926, he was hired as an edge trimmer at the Bluff City plant of the International Shoe Company. In 1941, Wiggs became a union organizer for the United Shoe Workers of America (CIO) in the Hannibal plants and elsewhere. Because of his effectiveness, the CIO hired him as a national field representative in the tri-state district bounded by Kirksville and Moberly, Missouri, Keokuk, Iowa, and Pittsfield, Illinois. While sitting in a parked car in Pittsfield, he was dragged out of the car, attacked, and beaten by a gang of vigilantes that included anti-union employees at the local plant of the Hamilton-Brown Shoe Company. The attack put him in the hospital, but he recovered and remained undeterred in his mission. Like his sister, Mattie, he was committed to helping the needy, but his commitment took the form of unionizing workers to achieve higher wages, improved working conditions, and a better life.

In 1946, when the CIO launched “Operation Dixie,” a major drive to unionize workers across racial lines in the South, Wiggs was assigned to Jonesboro, Craighead County, in the Arkansas Delta. Later, he was transferred to the area around Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. In an Arkansas Delta moment of reflection, Wiggs acknowledged that labor organizing posed a threat to his personal safety, especially in the South, but his class consciousness was stronger than his fear of personal harm. “But you forget all this when you go out and see some of the workers living in shacks and houses ready to fall down,” he said, “and four or five small children, ragged and not enough to eat, with the father and mother doing the best they can on the wages they receive. It makes you forget about yourself and any danger of being beat up.”

The images of Delta poverty described by Wiggs bore a resemblance in some ways to the images of his family’s shanty in Monkey Run described by Frank L. Kelly in 1911. The Hannibal area occupied a special place in Wiggs’s heart. He was particularly proud to have played a major role in unionizing the town’s shoe workers into the CIO. After retiring in 1957 as the result of serious heart problems and ulcers, he and his wife Mildred moved to Hannibal, joined the Church of the Nazarene, and lived at 2520 Fulton Avenue.

On January 16, 1962, Wiggs died of head injuries he sustained when his car slid out of control under icy conditions and struck a tree as he was driving down Fulton Avenue toward town. I am writing a book on Hannibal shoe workers that will include much more material on Wiggs and his family. If you are related to him, I would love to hear from you.

Leave a comment