By Gregg Andrews

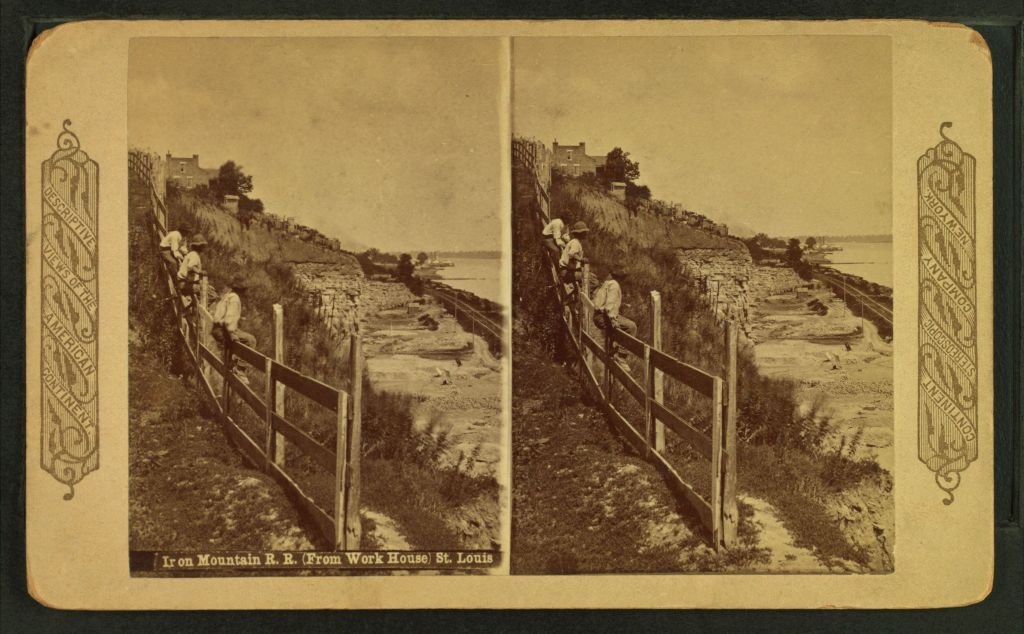

Fishing out “floaters” from the Mississippi River near St. Louis’s Workhouse Landing was a somewhat familiar, if disturbing, occurrence at the turn of the 20th century. So, too, were attempted escapes from the notorious Workhouse on the bluff known as Point Breeze on South Broadway. At the bottom of the bluff lay the Workhouse quarry, a steamboat landing, and the shantyboat settlement of “Chickentown.” The tragic story of how a traveling insurance agent from Des Moines ended up as an inmate in the St. Louis Workhouse and as a corpse in the river gives us an unsettling look at the city’s Police Court system of justice at the time.

Michael C. Bennett, age 36, was from a well-respected family in Des Moines. He checked into St. Louis’s Jefferson Hotel to attend the Democratic Party’s 1904 national convention in the Exposition and Music Hall from July 6 to July 10. While in St. Louis, he fell seriously ill. The illness prolonged his stay, and he ran out of money. When the hotel clerk grew suspicious and asked him to pay his bill, Bennett wrote a draft on his brother’s account in Des Moines. To make sure the draft was legit, the clerk sent a telegram to Peter Bennett, who was out of town and didn’t see the telegram till it was too late to help his brother. In the meantime, the clerk summoned a police officer, who arrested Bennett for loitering about the hotel after the clerk asked him to leave. Fined $25 for trespass in Police Court, Bennett tried to explain that he was waiting for his brother to okay the draft he made out to the hotel, but the judge cut him off and banished him to the city rockpile because he couldn’t pay the fine.

Bennett donned Workhouse garb on July 28, 1904. Sentenced to work off his fine at a rate of fifty cents per day minus room and board, he was quickly swallowed by the medieval river monster otherwise known as the city Workhouse. It swallowed a good many others in its day. Weakened by illness and unaccustomed to hard labor, Bennett went downhill fast under the strain of confinement in overcrowded cells with nasty food and abusive guards. After three weeks of breaking up rock in the quarry, he was down to skin and bones and desperate, having shed seventy pounds since his illness and imprisonment.

While laboring in the pit of the quarry on August 18, 1904, Bennett reached a breaking point. He couldn’t take it anymore. Seeing an opportunity, he made a mad dash for freedom. He fled north along the Iron Mountain Railroad tracks, but armed Workhouse guards spotted him from up above, clambered down the bluff, and headed him off. Other guards sealed off his escape route from the south. Bennett was boxed in. Solitary confinement on bread and water in the medieval “bull pen,” plus an extended sentence and a good beating likely awaited if he surrendered.

About fifty feet to the east lay the river, his only remaining option. In a split-second decision, he plunged in and disappeared under water before resurfacing farther out in the river’s current. He appeared to be struggling. With guards hollering and threatening to shoot him, he reportedly yelled, “I can’t make it. Send word to my folks.” Then, down he sank again for the final time, vanishing into the river’s dark abyss near the foot of Meramec Street.

Dynamite blasts in the river later brought Bennett’s corpse to the surface. Frank Bennett, one of his grief-stricken brothers, came to St. Louis to accompany the body as it was shipped back to Des Moines for burial, but the story doesn’t end here. Sadly, it contains an additional heartbreaking dimension. For further details and the rest of the story, see my recent book available @LSU Press.

Note: The featured image of the quarry at Workhouse Landing is from the William G. Swekowsky Notre Dame College Collection, South St. Louis Civic Buildings, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis, circa 1912.

Leave a comment