By Gregg Andrews

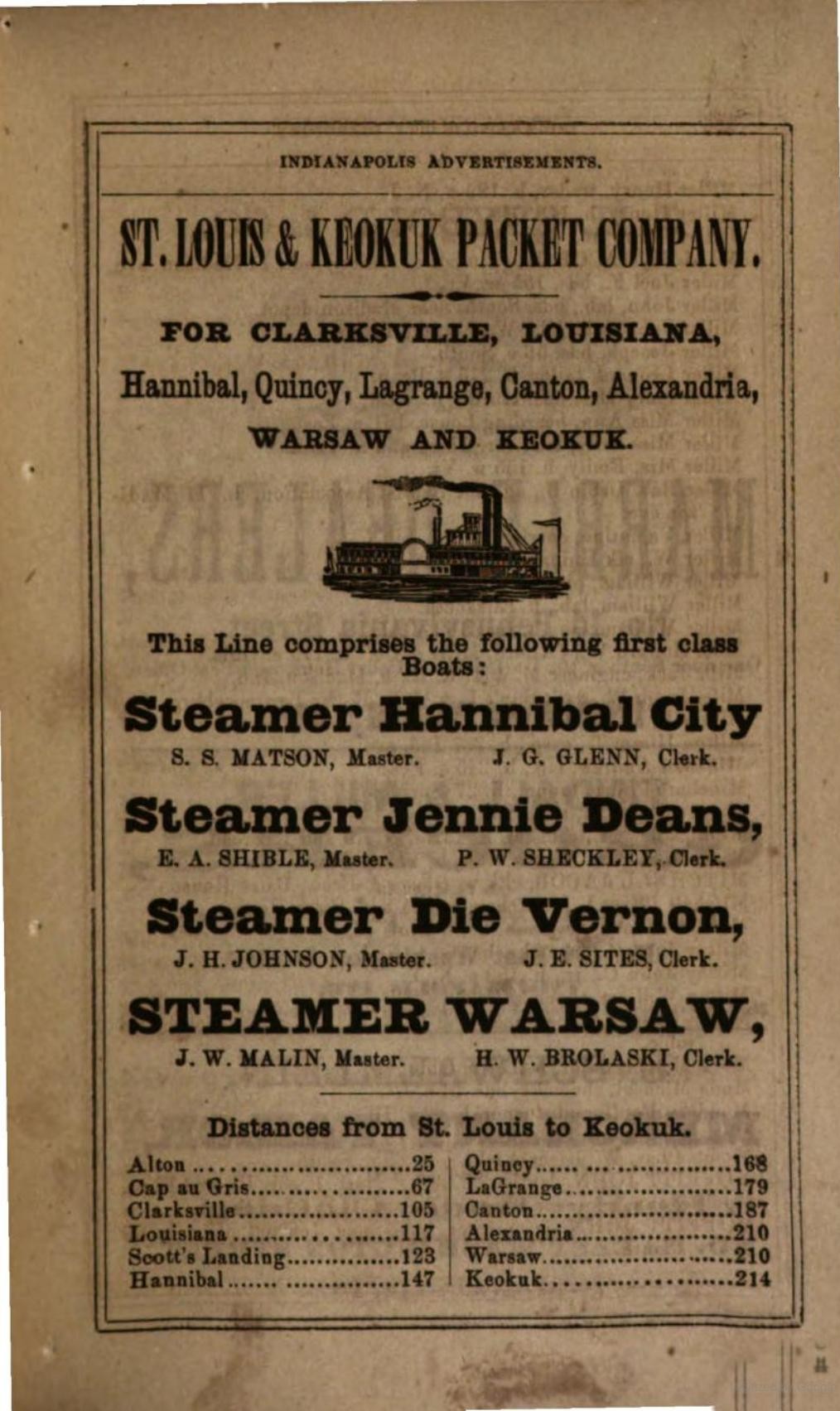

The Hannibal City was a sidewheel steamboat named in honor of Missouri’s leading port north of St. Louis. The sidewheeler belonged to the fleet of the St. Louis & Keokuk Packet Company. On January 1, 1842, a group of St. Louis investors formed the packet company to operate on the Upper Mississippi River. The main investors were John S. McCune and James E. Yeatman, and its first boat was the Die Vernon, a sidewheeler captained by Neil Cameron, of Saverton. The company prospered, securing the U.S. Mail contract in 1844 and adding new boats as disasters, costly explosions, and wharf fires took their toll. In 1857, the Hannibal City’s hull was built in Madison, Indiana, and then towed from Louisville to St. Louis, where the foundry of Samuel Gaty and John S. McCune added her machinery and cabin decorations. With an emphasis on beauty and speed, she was designed for passenger traffic rather than freight hauling between St. Louis and Keokuk. With Scott S. Matson as commander, F. S. Lee and Jack Kneedler as first and second clerks, and W.A. Matson and William Howard as pilots, the Hannibal City was put into service in March 1858. The Hannibal Daily Messenger touted her as the “Queen of the Western Waters.”

A month after the Hannibal City’s maiden voyage, she pulled away from the packet line’s wharf boat in St. Louis on April 22 at about four o’clock in the afternoon. She was bound for Keokuk. Prior to departure, Capt. Matson told the mate to make haste so that the Hannibal City could leave on time. About 100 yards ahead of her was the Ocean Spray with a cargo of freight, a “small head of steam,” and about forty passengers bound for Peoria on the Illinois River. Capt. Waldo Marsh was the commander and part owner of the fast Ocean Spray. Rumors had circulated that he was eager for a race with the Hannibal City. Here was a chance. The boats continued north at considerable speeds as the distance between them narrowed.

To increase speed, the Ocean Spray used rosin to ignite and increase the combustion of wood and coal. As the Hannibal City drew closer about five miles north of St. Louis, the Ocean Spray‘s officers took a risky step by using turpentine to gain added speed. Capt. Marsh consulted with the engineer, William J. Spargo, who downplayed the danger if turpentine was used properly. The mate and several deckhands retrieved a barrel of turpentine from the boat’s hold, broke it open, and filled a bucket from it, using an attached rope. Pieces of wood and coal were then dipped or soaked in turpentine and tossed into the fiery furnace. The barrel of turpentine sat no more than six feet from the furnace doors. When a fireman accidentally pulled out a small piece of burning coal with his rake, it ignited a raging fire. The Ocean Spray, as soon as the fire broke out, headed for shore in high winds. The horrible disaster killed approximately two dozen people and led further to the burning of the Star of the West and the Keokuk steamers. After an investigation, the United States Commissioner stripped engineer Spargo of his license.

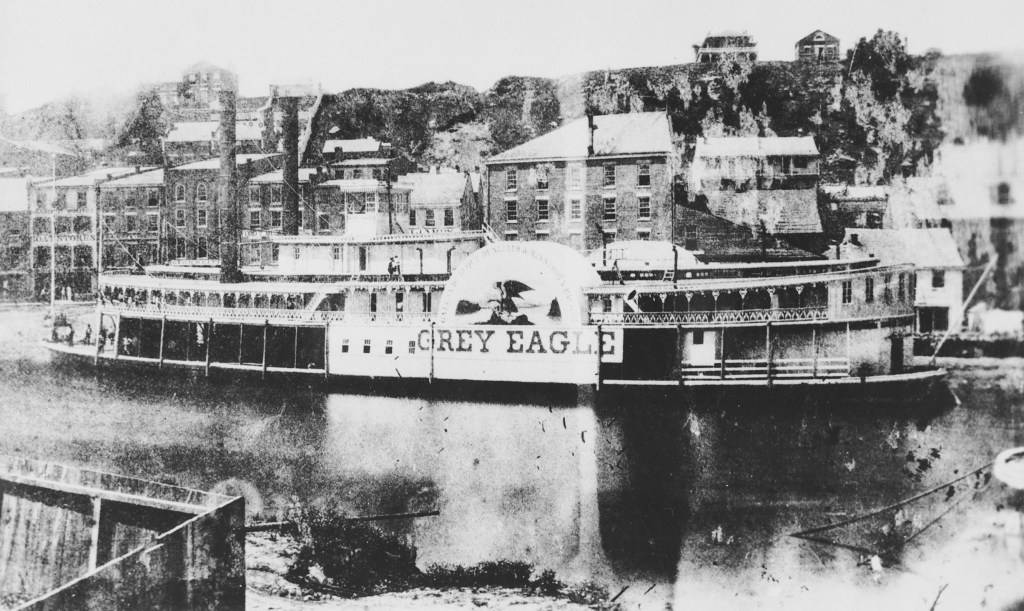

Capt. Matson and the crew of the Hannibal City denied that they were racing, but newspaper accounts disagreed. In the interest of public safety, newspapers often urged steamboat owners to refrain from racing, but the practice continued. On June 26, 1860, the Hannibal City nosed out the Grey Eagle, arriving in Keokuk two minutes before her racing opponent.

When the Civil War broke out, the Hannibal City continued its packet runs on the Upper Mississippi, but in April 1862, the boat was pressed into service on behalf of the Union. After the surrender of Confederate forces at Island No. 10, the Hannibal City transported members of the 11th Missouri Volunteer Infantry from New Madrid to Mosquito Point, Arkansas. A few days later, the boat took them up the Tennessee River to Hamburg Landing to join the Army of the Mississippi. Upon completing the assignment, the Hannibal City resumed her schedule on the Upper Mississippi, but five months later, she ran onto a sunken log raft just below the town of Louisiana and sank in seven or eight feet of water. No lives were lost. All the machinery and upper works were salvaged, but the accident ended the four-year life of the Hannibal City.

Sources: W. Craig Gaines, Encyclopedia of Civil War Shipwrecks, LSU Press, 2008, p. 96; Indianapolis Directory and Business Mirror for 1861, p. 196; "Report on the Finances," October 25, 1858, p.71, Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury of the State of the Finances, 1858; Dennis W. Belcher, The 11th Missouri Volunteer Infantry in the Civil War: A History and Roster, 2011, pp. 45-46; John Thomas Scharf, History of St. Louis City and County, vol. II, 1883, p. 1115; Daily Missouri Republican, May 3, 1857, p.2; Louisiana Journal, September 11, 1862, p.3; LaGrange National American, March 20, 1858, p.2; Hannibal Daily Messenger, April 24, 1858, p.2, and June 29, 1860, p.3. Daily Gate City (Keokuk), September 7, 1857, p.2; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 3, 1858, p.1; The Weekly Pantagraph (Bloomington, IL), April 28, 1858, p.3.

Leave a comment