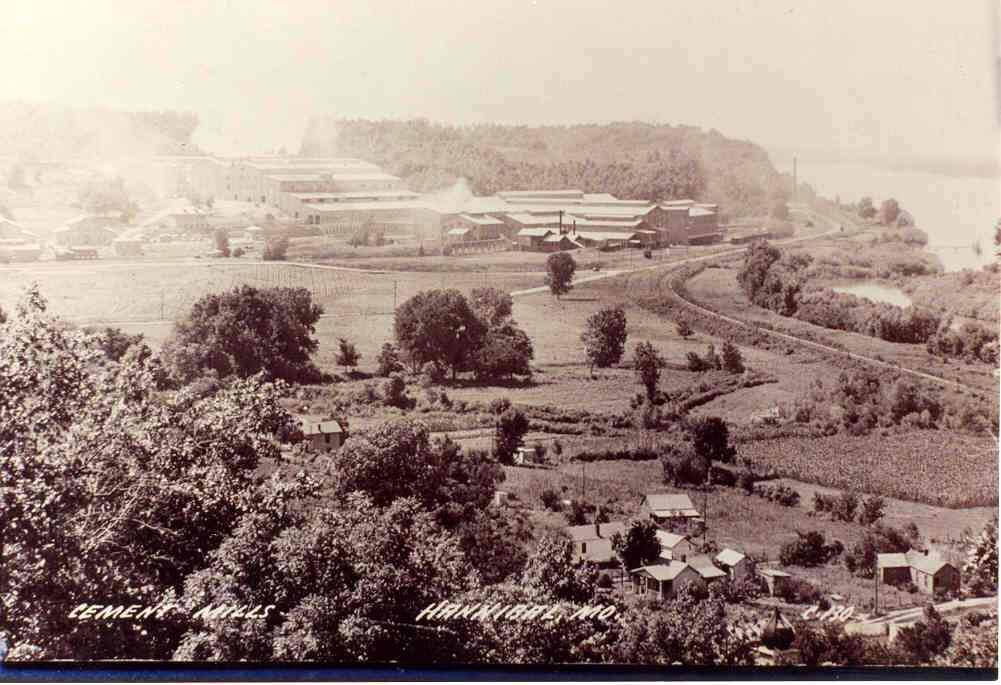

On Saturday, May 13, 1905, Pearl Pryor boarded a train from Barry, Illinois, to Hannibal, Missouri, having made the most fateful decision in her young life. Four or five months pregnant, she was about to undergo her second abortion, undeterred at age 18 by the fact it was dangerous and against the law. In Hannibal, she caught the Atlas Portland Cement Company’s shift train south to the cement plant. Ilasco, the two-year-old, rough-and-tumble community on the perimeter of the plant in Ralls County’s Marble Creek Valley, was her destination. At the time, Ilasco resembled a mining camp with roaring taverns, knife fights, and crowded boardinghouses. Transient men from southern and eastern Europe and surrounding areas of northeast Missouri and western Illinois vastly outnumbered women. “They had a fight every night,” recalled Ruby Douglas Northcutt. “The jail was full down here.”

It wasn’t Pearl’s first trip to the town of company barracks, tar paper shanties, and shantyboats on the west bank of the Mississippi. Until a few weeks earlier, in fact, she boarded in the Ilasco home of Mary Perkins for several months before returning to her father, Silas A. Pryor, a farmer in Barry. The unidentified man who impregnated Pearl likely walked the dust-covered roads of Ilasco or the streets of Hannibal.

Less than two years earlier, Pearl married James Holland in the nearby river village of Saverton to the south, but the marriage ended fast. She learned he was a bigamist. Left pregnant at age sixteen, she performed a risky, self-induced criminal abortion. Charles E. Beavers, a physician in Barry, treated her for complications related to its aftereffects in September 1903. Pearl might have lied to protect the person who performed the abortion, but according to Anna Rupert, of Ilasco, Pearl showed her a six-inch piece of wire she used on herself to abort. Pearl made clear she’d rather risk death than give birth to a child under the circumstances.

When Pearl stepped off the work train in Ilasco on May 13, 1905, there at the depot to greet her with a loving kiss was “Dr.” Ida Belle Clark, a friend well-known to women of the town. Pryor had written her a letter a few days earlier. Clark was a graduate of the new American School of Magnetic Healing at Sidney Weltmer’s controversial but highly popular Institute of Suggestive Therapeutics in Nevada, Missouri. The practice of magnetic healing combined the use of hypnotic suggestion and clairvoyance to treat just about any physical or mental affliction under the sun. Patients and devoted followers and students flocked to Nevada in search of alternative approaches to healing. It’s unclear if Clark took mail-order courses from Weltmer, or if she boarded at the institute, where he treated patients and where disciples at a cost of $100 attended three lectures per day for ten days. When “Dr.” S.E. McCreary, a magnetic healer, opened an office near the riverfront in Hannibal in 1900, he soon hired Ida to assist him in his practice.

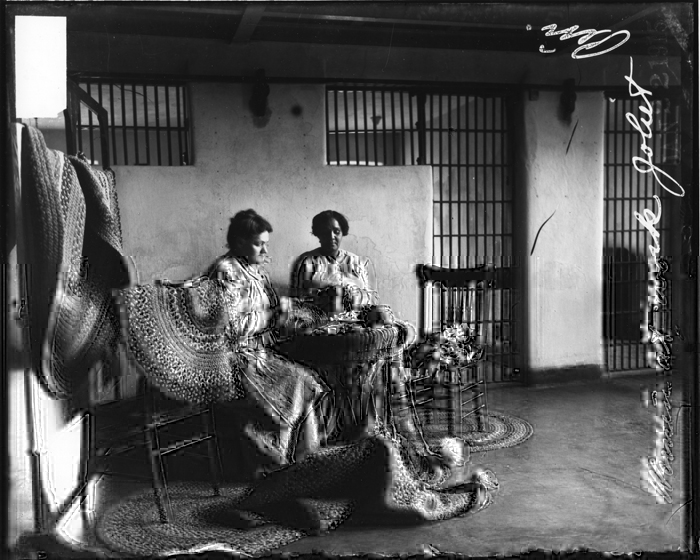

Clark, a native of Saverton, was the daughter of Mary E. (Meyers) and James K.P. “Polk” Elzea. At age 14, she married William Walter Steers in 1889, but after their marriage fell apart, their four children were raised by Ida’s Ralls County parents. In Hannibal, Ida lived on the riverfront at the foot of Bird Street and kept an office where she offered services as a magnetic healer. On the day after her divorce from Steers in March 1901, she married Robert E. Duffy, but he went to the Missouri penitentiary for grand larceny in October 1902. While Duffy was in prison, she obtained a divorce and shared a shantyboat with Henry Clark in Ilasco. Upon release from prison in January 1905, Duffy went to Ilasco and threatened to have them arrested on charges of “rooming.” Ida whipped out a revolver and ran him off, but she and Henry, who had served long prison stretches for grand larceny under Missouri’s habitual criminal statute, quickly tied the knot to avoid legal problems.

The Clarks moved their shantyboat across the Mississippi River to Four Mile Island, near the Illinois shore in Pike County. With plans for a garden in a cleared section of the heavily wooded island near their boat, they grazed a sow and a few pigs. Magnetic healing wasn’t the only business Ida drummed up in Ilasco as she and Henry went back and forth across the river. Through the women’s grapevine, she let it be known she could perform an abortion or induce a miscarriage by means of instruments or medicines. Henry, too, spread the word about her services, urging the husband of an area woman, “If your wife will listen to Ida you folks won’t have any more children.” (Ida Clark et al v. The People of the State of Illinois, Supreme Court of Illinois, opinion filed Dec. 22, 1906, p. 563).

On May 13, Pearl and Ida walked from the Ilasco depot to the riverbank, where Henry waited in a skiff to row them to their one-room shantyboat moored on Four Mile Island. Three days later, Pearl died on the boat from a botched abortion under primitive, unsanitary conditions. An inquest held on the island and a post-mortem examination in Hannibal concluded that a sharp instrument which was intended to abort the fetus missed the womb and pierced Pearl’s bladder instead, causing an excruciating death from shock or peritonitis. The instrument was never found. Although the Clarks insisted that Pearl’s death came at her own hands, a Pike County jury convicted them on charges of 2nd-degree murder on May 3, 1906. They were sentenced to fourteen years in prison. The Illinois Supreme Court upheld the convictions.

Dora Lyman in Ilasco, ca. 1910. Her sister, Lizzie Lester, age 22, died of pneumonia after a criminal abortion in 1909. Soon after Dora's third marriage, she died in 1919 from a uterine infection linked to an STD that spread to her ovaries and Fallopian tubes. Photo courtesy of Author.

With limited or no access to birth control or even educational materials about birth control, some desperate women turned to desperate solutions, willing to risk gossip, condemnation, criminal prosecution, and even death to end unwanted pregnancies and limit family size. In late May 1905, just two weeks after Ida Clark met Pearl Pryor at the depot in Ilasco, newborn twins–a boy and girl not much more than an hour old–were abandoned on the Ilasco public road and in the weeds nearby. The infants were unclothed, unfed, and crying in the night air when passersby heard the desperate sounds and rescued them.

(Major sources consulted: Gregg Andrews, City of Dust: A Cement Company Town in the Land of Tom Sawyer (University of Missouri Press, 1996), pp. 244-245; Ida Clark et al v. The People of the State of Illinois, Supreme Court of Illinois, opinion filed Dec. 22, 1906, pp. 554-568; United States Federal Censuses, 1880-1920; R.L. Polk City Directories (Hannibal); Patrick Brophy, “Weltmer, Stanhope, and the Rest: Magnetic Healing in Nevada, Missouri,” Missouri Historical Review 91 (April 1997): 275-294; Leslie J. Reagan, When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and Law in the United States, 1867-1973 (University of California Press, 1998); American School of Magnetic Healing and J.H. Kelly, Appellants v. J.M. McAnnulty, November 17, 1902, United States Supreme Court Reports, book 47, pp. 90-97; Hannibal Courier-Post; Ralls County Times; Quincy Daily Journal; Criminal Record, book 5, Pike County, Office of the Circuit Clerk, Pittsfield, IL ).

Leave a comment