By Gregg Andrews

Travel writers who visit river towns in the Mississippi Valley often give us candid snapshots of waterfronts, and at times they offer a frank perspective on life and labor on the levee. As the boyhood home of Mark Twain, Hannibal has drawn more than its share of writers who tour the landmarks that celebrate the town’s famous author. Recently, I read a brief traveler’s account of a visit to Hannibal in 1929 that particularly caught my eye. It did so because Hannibal is my hometown and because waterfront communities have been the subject of my research.

The writer was Father William Schaefers, editor of the Catholic Advance, the official organ of the Diocese of Wichita, Kansas. Father Schaefers, a widely traveled German immigrant, often wrote feature articles and popular Travelogs. He was also a lecturer who did radio broadcasts under the auspices of the Knights of Columbus’s Catholic Action Committee, and he served as Chaplain of the St. Francis Hospital in Wichita.

On a trip to Hannibal, Father Schaefers toured the cave made famous by Mark Twain and other points of interest, including Lover’s Leap. Father Schaefers published parts of his Travelog with commentary in the Catholic Advance and the Wichita Beacon. In a column, “Stray Bits,” published in the Catholic Advance on December 14, 1929, he noted that on November 13, he visited “Hannibal’s oldest grocery, owned and operated by two old spinsters—millionaires.”

My interest piqued as I read his description of the riverfront store at 400 N. Main Street: “I have never seen a store like it. Cluttered with heaps of cheap groceries of every description, shelves sagging under the weight of canned goods of ancient vintage, flour piled high in sacks on the plank floor, candy greasy with age, and cheese that swells and moves! Foodstuff rotting in barrels and in sacks, dirt and flies and mice.”

“Who trades here?” Father Schaefers asked. “The ‘river rats’ and the negroes—looking for bargains,” he answered. “The old ladies sell their goods at low prices. I was told that they buy ruined stock and half-spoiled groceries and vegetables.” He also called attention to a built-in vault with iron doors in a corner of the store, which at one time reportedly served as Hannibal’s first bank. Inside the vault, the sisters kept faded documents and money sacks. Above the door to the vault, there hung an old musket picked up years earlier from the Gettysburg battlefield. The sisters were surrounded by musty newspaper clippings and bundles of old letters. “These millionaire women, spending the day in their smelly store, are curiosities,” Father Schaefers observed. “They are known far and wide, and are shrewd stock gamblers, so they say.”

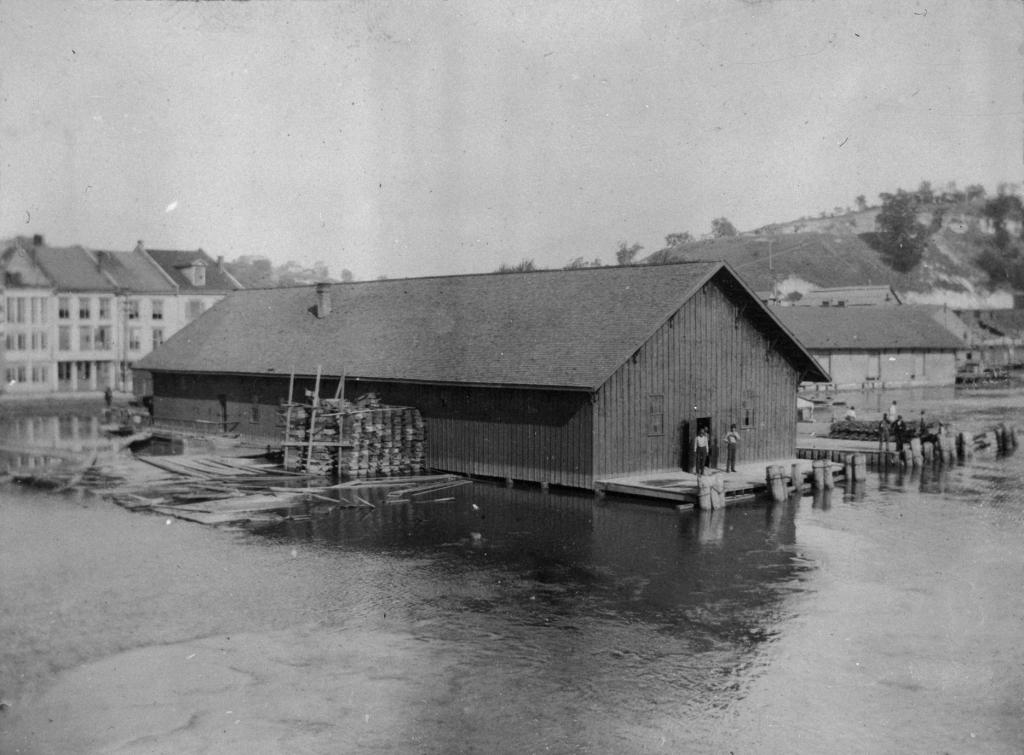

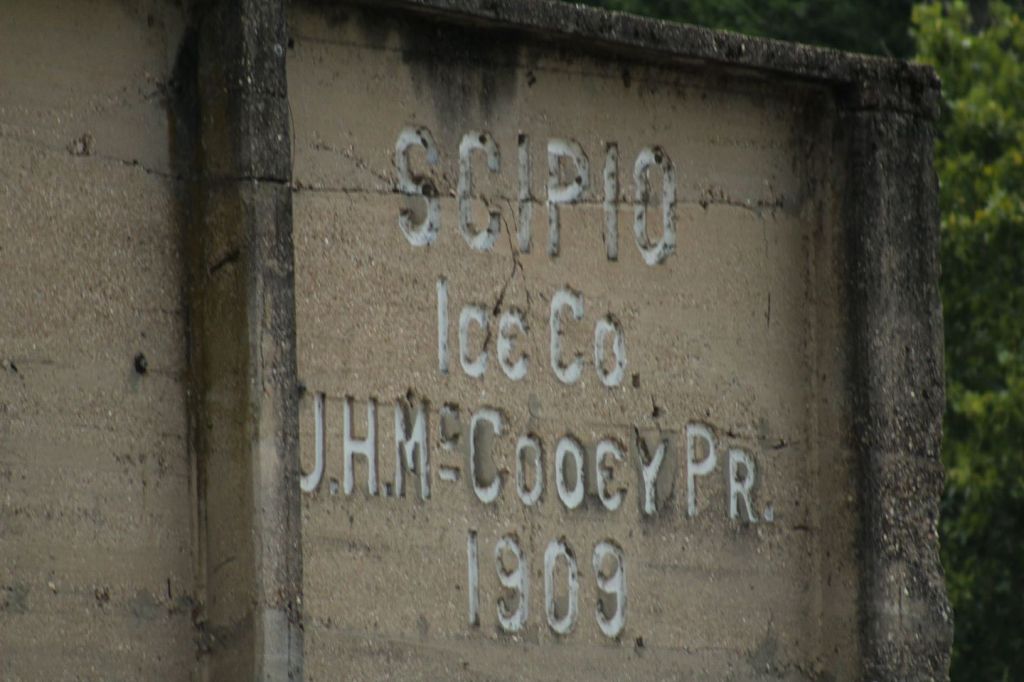

Father Schaefers did not reveal the identity of the sisters, but they were Mary (Minnie) E.A. McCooey and sister, Anna T. McCooey, prominent businesswomen and wealthy philanthropists in Hannibal. Daughters of merchant Irish immigrants, they and their Oxford-educated brother, James H. McCooey, added to the family’s businesses that were sustained and expanded by their mother after the death of their father in 1869. The sisters and brother incorporated the Hannibal Cereal Company in 1896, and two years later, James began construction of a large grain elevator with a storage capacity of 60,000 bushels on Bridge Street on Hannibal’s north wharf. Neither the sisters nor James married. After their mother died, the three continued to live in the family home at 115 N. Fifth Street while they tended to their grocer and ice business on the riverfront. After a fire destroyed their icehouse in 1908, James built a fireproof replacement made of concrete in 1909, about two miles north of Hannibal in what once was the riverfront Port of Scipio.

In a case filed by Marion County Prosecuting Attorney Eugene Nelson in the Hannibal Court of Common Pleas in 1906, the McCooey Company avoided revocation of their business franchise after charges it was part of a local “ice trust” conspiracy to fix prices, limit competition, and to gouge consumers. During the buildup to United States entry into the First World War, James, a prominent Democrat, died of apoplexy at age 57 on March 2, 1917, a month before the U.S. declared war on Germany. According to George J. Menger, a Palmyra farmer and acquaintance, James worried that the war might ruin his business ventures. When Menger got the news of his death, he wrote a letter to the editor that appeared in the Marion County Herald on March 21: “The announcement. . . puts me in mind of the last conversation I had with him last fall. McCooey being a Democrat and against the war said the men in the trenches weren’t so much, but that the men who had the property would have to pay the expense of war and they would have to be the sufferers.”

In the Centennial History of Missouri (1921), Walter Barlow Stevens described the McCooey holdings as “the heaviest property holding estate in that part of the country” (vol. 4, p. 492). James left a large personal estate as well as extensive real estate and insurance stockholdings in St. Louis, Hannibal, and the Palmyra area. Mary, and especially, Anna continued to operate J.H. McCooey and Co., the waterfront grocer business, which also sold feed, flour, and fertilizer as well as cement. In 1920, the United States Department of Agriculture included the company on a list of firms selling adulterated seed to area farmers.

In the mid-1920s, the sisters turned to philanthropy. They donated $125,000 in 1925 to build a Catholic high school in Hannibal to honor their deceased brother. Dedication ceremonies for McCooey School, which included all grades, took place on October 20, 1926. The distinguished school remained open for about forty years.

When Anna died intestate at age 70 on September 19, 1931, cousins in St. Louis brought insanity proceedings against Mary, challenging her right to inherit her sister’s estate of $125,000. The relatives failed in their effort. When Mary died at age 76 on September 11, 1934, they tried but failed again to break her will and last testament on grounds of mental incompetence. The “millionaire spinsters” left large personal estates and real estate, including the Windsor Hotel, where Mark Twain stayed on his final trip to Hannibal in 1902. Mary, who seemed more devoted to church matters than business transactions, left sizeable bequests in her will to Hannibal’s schools, public library, hospitals, and charitable community organizations.

The Hannibal riverfront was good to the McCooey family, which in turn was praised for its philanthropy and leadership in the movement to build modern river terminals in the town. James was appointed by the mayor in 1910 as a delegate to the Deep Waterways Convention in St. Louis. The family amassed a fortune and played an important role in the development of Hannibal and the Upper Mississippi River Valley.

The McCooey’s waterfront businesses relied on cheap labor provided by shantyboat residents and casual dock laborers. According to Father Schaefers’ brief description of the McCooey sisters and their riverfront store and customers, they also sold cheap, rotting food to the town’s “river rats” and poor Black people. Father Schaefers, perhaps unintentionally, called attention to the deep disparities of wealth and the racial divide in segregated Hannibal at the beginning of the Great Depression.

(Sources available upon request).

Leave a reply to John Wingate Cancel reply