By Gregg Andrews

“Who’s Solomon Dixon?” That’s the question the fictional R & B singer, Phoenix, asks herself after falling asleep in Los Angeles and waking up a century earlier in the parlor of Dixon’s home in Sedalia, Missouri. In Joplin’s Ghost (Atria Books, 2005), a historical novel by acclaimed writer Tananarive Due, Phoenix takes note of every vivid detail in Dixon’s home. In a surreal, dream-like experience, Phoenix looks on as Dixon urges “Scotty” to play the family’s Emerson Square Grand piano for Freddie, Joplin’s young but ailing, fast-failing new bride from Little Rock. Dixon has “hollowed cheeks, large ears and a slight overbite that made him look vaguely displeased even when he wasn’t,” writes Due (p. 273). Phoenix is surprised to hear Dixon call ragtime pianist and composer Scott Joplin, “Scotty.” Dixon’s home is where Freddie Alexander Joplin died shortly after she stepped off the train in Sedalia with “Scotty” and a worsening cold in 1904. The home where Joplin sometimes received his mail.

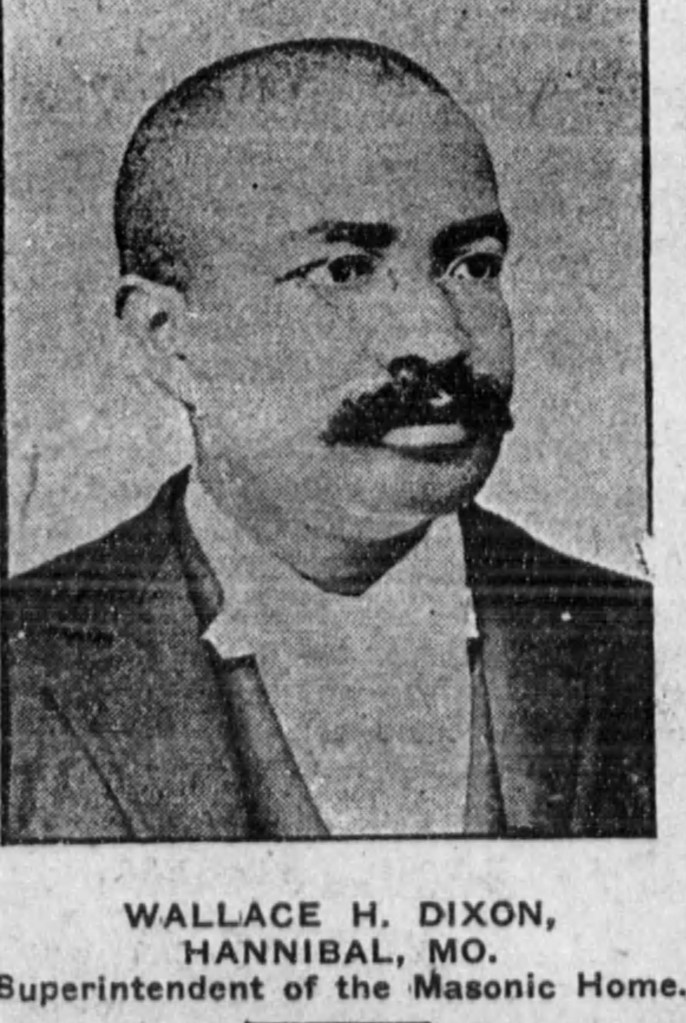

Several months ago, I, too, asked myself for the first time, “Who’s Solomon Dixon?” I asked not as a novelist, but as a historian. At the time, I was researching the history of Wallace H. Dixon, a prominent educator in Missouri’s segregated schools who spent nearly 27 years working in a Hannibal shoe factory. Between 1913 and 1919, he and his wife, Sarah [Taylor] Dixon, managed the Masonic Home in Hannibal, where Wallace also was the Associate Editor of a Black newspaper, the Home Protective Record. Sarah, too, was a former teacher, and their daughter, Thelma, shined as a talented pianist who taught in Hannibal’s segregated Douglass School until 1926. I had no knowledge of the connections between Scott Joplin and the Dixons in Sedalia when I began my research. Nor did I know that Wallace H. Dixon came from that same Sedalia family. I was writing a book on Hannibal shoe workers when a side trail of research led me to unearth the story of Wallace and his parents. All three were enslaved along the Missouri River in Missouri’s “Little Dixie.”

Solomon was born into slavery in Jefferson City on August 15, 1832. His father was Warren Dixon, a white Cole County farmer who was also his enslaver. Solomon’s wife, Hattie [Hogan] Dixon was a daughter of Richard Hogan, whose family held her in slavery. Hattie was born in nearby Otterville, Cooper County, on October 10, 1844. For several years, she and Solomon were leased out to the proprietors of the McCarty House and the Virginia Hotel in Jefferson City during the winter when the legislature was in session. At times, Solomon and Hattie worked together in the hotels. Hattie gave birth to their son, Wallace, on August 23, 1859. Legislators who boarded and ate at the hotels often tipped “Sol” for his services as a porter and waiter. Well-liked, he tucked away some of the tips as savings.

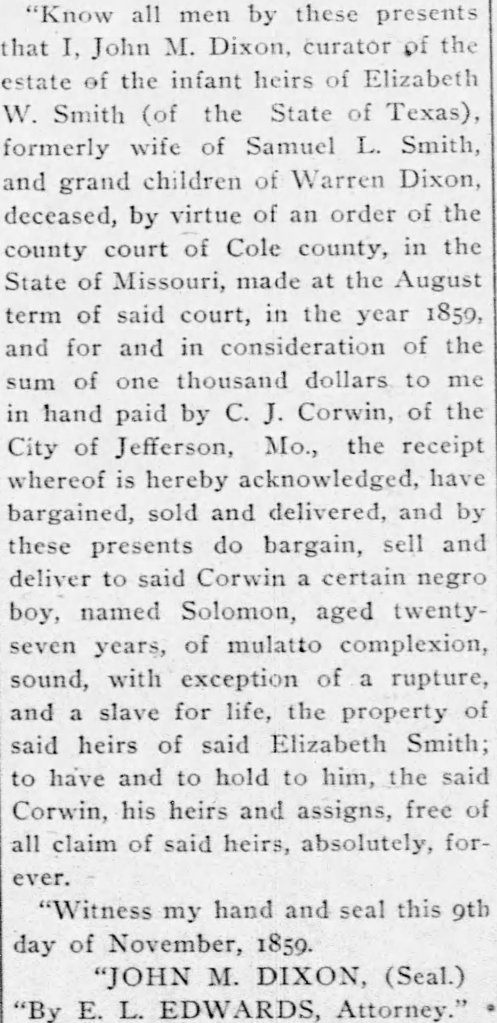

Around the time of Wallace’s birth, the death of Warren Dixon stirred concerns in Solomon that he would be sold and separated from Hattie and their baby in a curator’s estate sale. In charge of the sale was Solomon’s white half-brother, John M. Dixon. After listening to Solomon’s concerns, John Dixon consented that if Solomon found someone nearby to buy him for $1000, he would accept the sale. That “someone” turned out to be C.J. Corwin, a Democratic state printer and newspaper owner who moved from New York to Jefferson City in 1854. “In November 1859, he [Solomon] begged me to buy him and save him from being separated from his wife and boy,” recalled Corwin years later. “The privilege of finding a purchaser to his own liking had been given to him, and he said he had chosen me. We soon came to an understanding and I gave him a check.”

Solomon turned the official bill of sale over to Corwin, who emphasized that Solomon was “of high bred Southern lineage. . . Like his wife, he was almost white in color. . . and I have seldom met two more tender, true hearted creatures.” Whatever the “understanding” between Corwin and Solomon, dramatic events in Jefferson City swept them up in a much larger drama in May 1861. The political scene was chaotic amid reports that Union forces were en route from St. Louis to drive out Governor Claiborne Jackson and his secessionists. The steamboat landing in Jefferson City was filled with frenetic activity. In urgent discussions about where to hide the gunpowder stored at the fairgrounds, Missouri Adjutant-General Warwick Hough, a Jackson appointee, requisitioned the use of Solomon and Corwin’s team and wagon to transport the gunpowder elsewhere to be hidden from Unionist troops. According to Corwin, Solomon eagerly accepted the assignment, but Union loyalist guards intercepted him. When General Nathaniel Lyon took over the state capitol to prevent secession, Solomon and Hattie saw their moment and seized it, no matter Corwin’s “benevolent” paternalism. “My colored benefactions commenced giving their benefactor the ‘cold shoulder’ about the time the Union troops took the town,” he recalled. “Early in 1862, they had entirely ceased to recognize me. They did not wait for a proclamation of freedom or a constitutional amendment, but accepting the assurances of the soldiers that they were now ‘on top,’ they very deliberately set up for themselves.”

On account of Solomon’s thriftiness, “He was many dollars ahead when he took his flight to freedom,” Corwin further remembered. After freedom, Solomon continued as a porter at the McCarty Hotel. In 1872, he and a business partner opened a restaurant in Jefferson City, but the Dixons eventually bought a home and settled at 124 West Cooper Street in Sedalia. Solomon and Hattie emphasized the importance of education to their children. Wallace entered the preparatory department of Lincoln Institute in Jefferson City in 1873. A former waiter in Sedalia’s Garrison House, he graduated and became a teacher and principal of the Lincoln School in Warrensburg during the 1878-1879 school year. His sister, Carrie B. Dixon, was a classmate of Scott Joplin’s at George R. Smith College in Sedalia in 1896-97. One of nine students in the college’s first graduating class of ’97, she left Sedalia to accept a teaching position at the Lincoln School in Springfield, Mo. Anna Dixon Ferrell, a teacher in Sedalia’s Lincoln School, graduated from Lincoln University with a Bachelor of Science degree in Education in 1926. When it came to politics, the Dixons backed the local Democratic Party, a stance which endeared them to Sedalia’s white elites but angered Republican activists. Critics blasted Solomon and Wallace Dixon for supporting the party of slavery, secession, and suppression of full citizenship rights to freedmen. Wallace publicly returned the fire with skill and finesse, pointing out that the Republican Party had not lived up to its promises when it came to patronage, inclusion, and protection of civil rights.

When “Uncle Solomon” Dixon died at age 95 on August 18, 1927, several white Democratic local officials delivered eulogies. Members of the Methodist Church, where Dixon was a janitor for nearly thirty years, also turned out in force to praise him. A Jefferson City newspaper lauded his contributions to racial uplift in the face of adversity and obstacles. Hattie died at age 97 on February 24, 1942. Wallace, the only one of their five children born into slavery, suffered a light stroke at age 86 while at work in the Bluff City plant of the International Shoe Company in Hannibal in January 1946. He and Sarah, who had lost her eyesight about fifteen years earlier, were taken by their daughter to Los Angeles to be near her for care. Wallace died in Los Angeles on January 21, 1947, and Sarah, once described as an “elegant lecturer,” followed him on May 21, 1948.

Note #1: I will include much more material on Wallace and Sarah Dixon in my book in progress, “Shoe Workers in America’s Hometown.”

Note #2: On the role of C.J. Corwin, see his letters in the Jefferson City Courier, March 2, 1899, and the Jefferson City Tribune, May 28, 1903. On Scott Joplin, see the important work of Edward A. Berlin, King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era (Oxford University Press, 2nd ed., 2016)

Note #3: The featured image is of a group of students at George R. Smith College in Sedalia, circa 1900-1901, from the digital collections of the State Historical Society of Missouri.

Leave a comment